Nuance and Suggestion in the Tweety and Sylvester Series

By Kevin McCorry

By Kevin McCorry

A series of Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies released from 1947 to 1964.

Directed by I. (Friz) Freleng and Gerry Chiniquy.

Stories by Warren Foster, Tedd Pierce, Michael Maltese, Arthur Davis, John Dunn, Dave Detiege, Bill Daunch, and I. (Friz) Freleng.

Animation by Gerry Chiniquy, Virgil Ross, Ken Champin, Manuel Perez,

Arthur Davis, Emery Hawkins, Ted Bonnicksen, Tom Ray, Bob Matz, Art Leonardi,

and Lee Halpern.

Layouts by Hawley Pratt and Robert Gribbroek.

Backgrounds by Paul Julian, Phil DeLara, Carlos Manriquez, Irv Wyner, Boris Gorelick, and Tom O'Loughlin.

Voice Characterisation by Mel Blanc.

Music by Carl W. Stalling, Milt Franklyn, John Seely, Eugene Poddany, and William Lava.

An experimental pairing of two established cartoon characters in 1947 was so instantly successful that the duo's first film won an Academy Award.

Tweety and Sylvester are as enduring a twosome as any other that Warner Brothers' animation studios have created. Like Bugs Bunny and Elmer Fudd or the Road Runner and Wile E. Coyote, the Sylvester and Tweety team was the subject of a long-running classic cartoon series, along with vinyl records and print media- including illustrated magazines (i.e. comic books) distributed by Gold Key. Saturday morning U.S. television network compilations of Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies featured Tweety and Sylvester as prominently as the other pairs above mentioned. More than 50 years after his birth, Tweety continues to adorn T-shirts of girls who may empathise with Tweety's wide-eyed innocence and petite but spunky nature, while Sylvester as a plush toy, or as "spokes-cat" for Nine Lives cat food, or as a T-shirt or wall-poster image still nets considerable merchandise revenue. And after over 30 years in cartoon limbo, the duo were back in action in a weekly television series, The Sylvester and Tweety Mysteries (1995-8), courtesy of a new generation of talented animators at the revived Warner Brothers cartoon shop.

Tweety and Sylvester are as enduring a twosome as any other that Warner Brothers' animation studios have created. Like Bugs Bunny and Elmer Fudd or the Road Runner and Wile E. Coyote, the Sylvester and Tweety team was the subject of a long-running classic cartoon series, along with vinyl records and print media- including illustrated magazines (i.e. comic books) distributed by Gold Key. Saturday morning U.S. television network compilations of Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies featured Tweety and Sylvester as prominently as the other pairs above mentioned. More than 50 years after his birth, Tweety continues to adorn T-shirts of girls who may empathise with Tweety's wide-eyed innocence and petite but spunky nature, while Sylvester as a plush toy, or as "spokes-cat" for Nine Lives cat food, or as a T-shirt or wall-poster image still nets considerable merchandise revenue. And after over 30 years in cartoon limbo, the duo were back in action in a weekly television series, The Sylvester and Tweety Mysteries (1995-8), courtesy of a new generation of talented animators at the revived Warner Brothers cartoon shop.

The genesis of this funny cat-and-bird relationship was slow and haphazard. The two characters appeared solo in a number of films under the different styles of two directors. Tweety's first three appearances, devoid of feathers and baby-like in looks, were in Robert Clampett's "A Tale of Two Kitties" (1942), "Birdy and the Beast" (1944), and "A Gruesome Twosome" (1945), fighting other, rather dopey felines with typical Clampett wildness. Sylvester, meanwhile, starred in a series of Friz Freleng-directed cartoons as a loud-mouthed alley cat, fallible but not emphatically so, in his chasing of birds or his operatic tormenting of Elmer Fudd at all hours of the night.

The genesis of this funny cat-and-bird relationship was slow and haphazard. The two characters appeared solo in a number of films under the different styles of two directors. Tweety's first three appearances, devoid of feathers and baby-like in looks, were in Robert Clampett's "A Tale of Two Kitties" (1942), "Birdy and the Beast" (1944), and "A Gruesome Twosome" (1945), fighting other, rather dopey felines with typical Clampett wildness. Sylvester, meanwhile, starred in a series of Friz Freleng-directed cartoons as a loud-mouthed alley cat, fallible but not emphatically so, in his chasing of birds or his operatic tormenting of Elmer Fudd at all hours of the night.

In 1947, after Clampett had departed Warner Brothers with a fourth Tweety cartoon in early stages of production, Freleng was planning another Sylvester-vs.-bird film. In an earlier cartoon, Freleng had Sylvester chase a woodpecker, but now he saw Tweety as a likelier foe for the lisping cat. General producer Eddie Selzer, an appointee by the high echelons at Warner Brothers, knew little or nothing about cartoon production but nonetheless fancied himself to be an expert thereof, and he ordered Freleng not to pair Sylvester with Tweety, but to instead again use the woodpecker to contest Sylvester. In the ensuing argument, Freleng put his drafting pencil in Selzer's hand and said, "If you think you know so much, you should be doing it." He walked out of the studio, intending to quit Warner Brothers on the next day, but Selzer telephoned him at home in the evening and said, "Okay, do it your way." With that, Freleng directed the first film pitting Tweety against Sylvester.

The completed cartoon short, "Tweetie Pie", featured Tweety as an orphaned bird adopted on a cold winter's day by Sylvester's mistress. The personalities of the two cartoon stars "played off" one another with charm. Audiences loved their hi-jinks, and so did the Motion Picture Academy judges. "Tweetie Pie" won an Oscar. After that came two more energetic cartoons with the feisty canary and the scheming but not very brilliant cat. By 1950, their career was in its prime, and an average of 3 Sylvester and Tweety cartoons per year were produced for the next decade and a half.

Perhaps the reason for their appeal, along with that of all of the other animal stars of Warner Brothers' animated cartoons, is their human qualities. They may be animals with instincts and urges typical of their species, but they enact their impulses in a human manner. The endowing of animals with human thoughts and traits is common practice in animation, but the Warner Brothers studios elevated it to comic extremes. Tweety eats his bird seed with a spoon, gleefully bathes in a bathtub, sings lyrical songs, and, in a few of his early cartoons, attempts to woo "girl birds", while Sylvester salivates at the thought of a Tweety sandwich and employs human equipment and tactics to try to catch his prey. Both increasingly become "humanised", with complications for their original, animal nature, whose inclinations seem ignoble, a cause for guilt, in the human scheme of things.

A total of 42 cartoon shorts were made featuring this pair of characters, all of which were conceived and produced in one of the three main animation units at Warner Brothers, the unit of senior director Friz Freleng. And Freleng himself directed all but one of the films, the exception being Tweety and Sylvester's final appearance in theatrical cartoons, film number forty-two, which was directed by long-time Freleng animator Gerry Chiniquy.

Despite the seeming limitation in the notion of cat-pursuing-bird, the Tweety and Sylvester series was possibly the most versatile and varied of all of those done at Warner Brothers studios. The format was constant, that of Sylvester eyeing Tweety for lunch and chasing him for the duration of a cartoon, but the situations were varied and hilarious each and every time. The chase was stretched to nearly every Earthly setting possible: an ocean liner, a train, a park, a circus, a zoo, a beach, a farm, a snowbound cabin, a department store, a gangster's hideout, and such far-flung locales as Hawaii, Italy, and Japan, in addition to the conventional forest or U.S. city. The duo were also written into fictional scenarios like Little Red Riding Hood, Jack and the Beanstalk, and Jekyll and Hyde. They appeared in history as combatants in the American Civil War. And their chase parodied television series like Dragnet and Alfred Hitchcock Presents.

Various supporting characters were introduced to complicate Sylvester's chase so that it was less necessary for Tweety to act in his own defence and so seem more helpless. First, there was Granny, a gingerly matron with a preference for live, non-swallowed canaries and a thrash of her umbrella upon the head of any cat who would dare to "molest" her little birdie. Next was a bulldog by the name of Spike or Hector, who served, voluntarily or not, as Tweety's guardian and pummelled Sylvester any time that the cat came too close to the canary. Sylvester therefore sought to neutralise the canine and so had another cause for failed effort and disastrous consequences. Also a continuing character was a one-eyed, mute, orange tabby who fought Sylvester for culinary possession of Tweety, who had to run double-fast to escape both putty tats.

Not only did the settings and supporting characters change, but personalities underwent a gradual "progression". Adaptive "domestication" to a human world and human values and the problematic denial or repression of instinct are recurrent themes in this 42-cartoon series. Both characters, while continuing to act on animal urges, must conform to increasingly pervasive human ways as they become domesticated under the care of Granny in the country, or, with her or not, in the city. Tweety becomes human-like in his movements, running on two feet away from Sylvester rather than flying. Sometimes, he is able to flit upward to a shelf or some other place of safety, but rarely is he shown to fly capably for any duration. And in most cases when he tries to fly like an ordinary bird in the wild, he only does so with difficulty and falls flat on his face if he tries to maintain aloft motion.

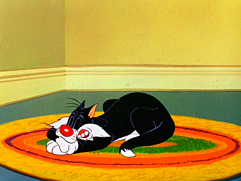

For his first films in which he was separate from Sylvester and directed by Clampett, Tweety was portrayed as loud-mouthed and merciless. Like nearly all of the Warner Brothers cartoon characters in that time period, he delighted in juvenile deviltry, actively tormenting any cats who happen to be nearby. Even in his first pairings with Sylvester, Tweety retains his physically aggressive personality, pounding Sylvester with mallets or sticks. But Freleng and his story man, Warren Foster, decided to reduce Tweety's aggressiveness and emphasise his smallness and give to him a milder, charming personality. Henceforth, Tweety was rather like Bugs Bunny, a mind-his-own-business-unless-provoked cartoon protagonist. He allowed Sylvester to defeat himself and delighted in seeing his assuming devourer receive appropriate punishment. Tweety, over this "evolution", flies less and less, so that by the time of "Sandy Claws" (1955), in which Tweety is surrounded by water after a tidal wave, he needs to manually paddle himself in his cage to dry land. And in "Tree Cornered Tweety" (1956), rather than just fly above deep snow on the ground, he has to apply spoons to his feet to act as snowshoes.

Over time, the Sylvester-Tweety conflict becomes less overtly physical and more psychological, especially for Sylvester, as more and more human adaptation requires him to quell his instincts. He must deny himself for his own sake, either because Granny has threatened to turn him into violin strings, or because he has lost some of his nine lives in his chase and is apt to lose them all if he persists, or because it has been explained to him that canary-craving is as self-destructive as human weakness for alcohol, and that abstinence is the best policy. Sylvester must restrain himself. Like man, Sylvester has become "domesticated", expected to live by thou-shall-not-kill. And he sometimes has to defend the canary that he craves.

He is indoctrinated to the virtues of the human world yet cannot transcend his catly instinct to eat birds. With this comes guilt surrounding his Tweety-hunt. Whereas earlier, he was not able to snatch Tweety due to his overeager ineptitude, in later cases he is impeded because he has become increasingly civilised and forced either by Granny or by his own conscience to adhere to the killing-is-wrong code of conduct. Sylvester has become "human", resulting in complexes, contradictions between instinct and decency. His relationship to Tweety has become a combat between old ways, the ones that tie Sylvester to others of his feline "clan"- panthers, tigers, and lions- and the civil, sociable mores of the human world to which he has become adapted.

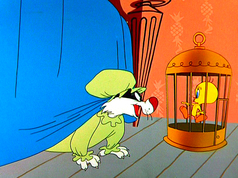

The Oscar-winning "Birds Anonymous" is the most famous portrayal of this conflict in the psyche of Sylvester. Made in 1957, 10 years after their first cartoon together merited recognition by the Motion Picture Academy, this Sylvester-Tweety series entry his been noted in most serious studies on Warner Brothers animation as a parable for human weakness for food, liquor, or sex. Sylvester begins the cartoon with the dark, sinister intent of eating Tweety. He pulls down the window shades, closes curtains, shuts out all light, all possible observation of his nefarious deed. Before he can swallow the helpless canary, one of the window blinds is raised and a mannerly fellow cat warns Sylvester off of the self-destructive taste for birds. Sylvester is initiated into an Alcoholics Anonymous-like club for cats "swearing off" birds. For the rest of the cartoon, Sylvester struggles to maintain composure as he tries to live with Tweety in brotherly love. He eventually loses control and "makes a grab" for the bird. "Just one little bird. Just one! No one will know the difference... Just one! Then I'll quit. I'll quit after one. Just one. Just one little bird!" When the other cat intervenes and preaches to Sylvester again about control of bird-eating urges, that cat kisses Tweety and is overcome with the same carnivorous cravings, only worse so: "It's been so long!" The kinship of these two felines under the stress of "domestication" is portrayed in a most human way: two brothers urging to binge after being on "the wagon" for an extended time period!

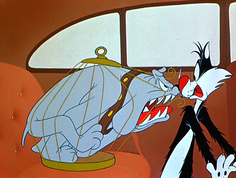

The psychological encounters are later in the cartoon series, culminating in "The Last Hungry Cat" (1961), an examination of human guilt in the mind of Sylvester, who thinks that he has swallowed and killed Tweety. In actuality, Tweety slipped out of Sylvester's mouth when Sylvester fell to the floor after seizing Tweety from a birdcage, leaving a few feathers in Sylvester's mouth. A Hitchcockian voice in the cartoon continually  chides Sylvester for his evil act and warns how Sylvester's conscience will induce mental collapse. Sylvester experiences exactly this, retreating to a decrepit hideout like a common criminal, pacing the floor to the point that it crumbles under him, chain-smoking and coffee-drinking in fear of going to sleep, and developing a red-eyed case of severe insomnia. He finally "cracks" and runs into the streets, confessing his crime, thankfully to find that he had not eaten the canary. But he resumes the chase anyhow, because he cannot help but enact his instincts released from the immediate strain of guilt.

chides Sylvester for his evil act and warns how Sylvester's conscience will induce mental collapse. Sylvester experiences exactly this, retreating to a decrepit hideout like a common criminal, pacing the floor to the point that it crumbles under him, chain-smoking and coffee-drinking in fear of going to sleep, and developing a red-eyed case of severe insomnia. He finally "cracks" and runs into the streets, confessing his crime, thankfully to find that he had not eaten the canary. But he resumes the chase anyhow, because he cannot help but enact his instincts released from the immediate strain of guilt.

The problem for Tweety caused by "domestication" is different. He has lost the ability to fly with freedom and grace like other birds, the ones in the wilds. He now has to move on his feet like a human; the inherent capacity for flight that connects birds to their earliest ancestors has, for Tweety, been almost entirely divested. Only the untamed birds seem to have retained flight with mastery, because they have remained in their original state of nature. For a domesticated bird almost unable to fly to somehow regain flight capability, is to revert, to "go back" to a less "civilised" condition, like in "Hyde and Go Tweet" (1960), wherein Tweety is able to reacquire the power of flight when he is reverted by Hyde formula into a prehistoric bird of prey, his evolved characteristics ungracefully removed.

Different but not contradictory is another case of Tweety regaining the ability to fly, by means of a jet-propelled cage, in "The Jet Cage" (1962). This clever modern contraption enables him to retain his evolved security and gentility and fly without reverting like he did in "Hyde and Go Tweet", by using technology to handle the mechanics of flight and to encase him in a protective, mobile "gilded cage". It seems that only by utilising modern instruments is he able to fly without reverting to a monstrous bird. But he is not really flying under his own wing-power, and his use of "The Jet Cage" likens him even more to humans, who need machines to fly.

Different but not contradictory is another case of Tweety regaining the ability to fly, by means of a jet-propelled cage, in "The Jet Cage" (1962). This clever modern contraption enables him to retain his evolved security and gentility and fly without reverting like he did in "Hyde and Go Tweet", by using technology to handle the mechanics of flight and to encase him in a protective, mobile "gilded cage". It seems that only by utilising modern instruments is he able to fly without reverting to a monstrous bird. But he is not really flying under his own wing-power, and his use of "The Jet Cage" likens him even more to humans, who need machines to fly.

Both characters' urges for inherent behaviour are corrupted when civilised directives are imposed over instinct. For Tweety, flight is an originally graceful ability that he has lost with "domestication", and so it has, for him, become a regressive trait only physically re-acquirable to a degree of competence by regressing ungracefully to a savage bird of prey. For Sylvester, bird-stalking, once an innocently savage trait of his feline species, has become regressive and a source of shame. It ties him to his voracious ancestor as Tweety's clumsy efforts at flight allude to his. Original states of nature have become regressive for both of these humanised "animals".

In "Tweety's Circus" (1955), Sylvester as a lark visits a closed-for-business big top and encounters the King of the Cats, a hot-tempered lion whose beastly character offends Sylvester's pride. Sylvester is not prepared to bow in the presence of such uncivilised "felineness", even though his own carnivorous instinct to hunt and eat Tweety is a descendant to the appetite of the beastly lion. What "paints" this cartoon as particularly fascinating is Sylvester's encounter with his ancestral "cousin" and his proud denial of its descendent traits in himself. But he reverts to the wildcat in himself every time that he acts on his urge to eat Tweety. In "Tweety's Circus", Sylvester confronts an external reminder of his wild, carnivorous species origins, and as a consequence, he projects his own self-loathing onto the lion by striking and angering the beast.

In "Tweety's Circus" (1955), Sylvester as a lark visits a closed-for-business big top and encounters the King of the Cats, a hot-tempered lion whose beastly character offends Sylvester's pride. Sylvester is not prepared to bow in the presence of such uncivilised "felineness", even though his own carnivorous instinct to hunt and eat Tweety is a descendant to the appetite of the beastly lion. What "paints" this cartoon as particularly fascinating is Sylvester's encounter with his ancestral "cousin" and his proud denial of its descendent traits in himself. But he reverts to the wildcat in himself every time that he acts on his urge to eat Tweety. In "Tweety's Circus", Sylvester confronts an external reminder of his wild, carnivorous species origins, and as a consequence, he projects his own self-loathing onto the lion by striking and angering the beast.

In the sequence of original Bugs Bunny/Road Runner Shows first broadcast in 1968-9, instalment number 24 containing "Hyde and Go Tweet" directly followed instalment 23 with "Tweety's Circus". "Hyde and Go Tweet" concerns Tweety's ancestral beast, brought out of himself by way of the Hyde formula. Tweety becomes an avian version of Hyde, a cross between the modern vulture or falcon and a large, prehistoric bird. In becoming the flying carnivore, Tweety regains the ability to fly and loses it when he transforms back to his modern form. He regains his ancestral ability but not the grace that once accompanied it, because in his domestication he has lost its innocence. It has become regressive in character, re-acquirable only by a "throwing off" of his genteel nature in the transformation, as Jekyll loses his civilised traits when he transforms.

In the sequence of original Bugs Bunny/Road Runner Shows first broadcast in 1968-9, instalment number 24 containing "Hyde and Go Tweet" directly followed instalment 23 with "Tweety's Circus". "Hyde and Go Tweet" concerns Tweety's ancestral beast, brought out of himself by way of the Hyde formula. Tweety becomes an avian version of Hyde, a cross between the modern vulture or falcon and a large, prehistoric bird. In becoming the flying carnivore, Tweety regains the ability to fly and loses it when he transforms back to his modern form. He regains his ancestral ability but not the grace that once accompanied it, because in his domestication he has lost its innocence. It has become regressive in character, re-acquirable only by a "throwing off" of his genteel nature in the transformation, as Jekyll loses his civilised traits when he transforms.

Actually, Tweety's transformations in "Hyde and Go Tweet" are the lurid imaginings of Sylvester's tortured mind, and the monstrous changes of Tweety in Sylvester's dream seem quite apropos after the encounter with the lions in the circus, a projection of Sylvester's deep-rooted sense of inferiority. Again, Sylvester's mounting guilt or shame, as a result of his domestication to civil life and the problem of his continued desire to eat Tweety, is preying on his mind, and he projects his growing awareness of the darker self in him onto Tweety in the nightmare (or day-mare?), with Tweety undergoing beastly transformations.

Certain parts of these cartoons are especially striking, for example the scene in "Tweety's Circus" wherein Sylvester pursues Tweety on the high wire, precariously moving forward with a balancing stick only to find Tweety on one of the edges of the stick. Sylvester attempts a grab for Tweety, loses his balance, and falls into the lion's mouth, devoured by the external representation of his monstrous feline self. Similarly, in "Hyde and Go Tweet", Sylvester is swallowed by the Tweety monster at the cartoon's climax. And in both cartoons, Sylvester locks himself inside either a cage or a room, thinking that he has secured himself from the ancestral beast symbolised either by the lion or by the vulture-like Tweety-Hyde, only to find that he has locked himself inside the cage or room with the beast which he is trying to escape.

In the case of "Tweety's Circus", Sylvester, after swallowing the key to a cage with him on the inside and his lion foe presumably on the outside, thinks, "Well, I guess that solves my lion problem." But when he walks further into the cage, he is surrounded by ravenous lions poised to devour him. Correspondingly, in "Hyde and Go Tweet", Sylvester, still unaware of the Hyde formula's effect on Tweety, thinks after carrying Tweety into a room and locking the door, that he has locked out the monstrous bird and thus solved his (and Tweety's) prehistoric bird "problem", but Tweety undergoes his transformation and, breathing menacingly with evil eyes, ingests Sylvester as the lion had done in the other cartoon.

It may be said to be something of a stretch to advance an argument for correspondence between "Tweety's Circus" and "Hyde and Go Tweet" to this extent. Suffice it to say, then, that in the former cartoon, Sylvester meets his own savage ancestor, and in the latter cartoon, he meets Tweety's- and the circumstances of both, however different in setting and effect, suggest a recurring motif- the bestial ancestor of both characters lurking either externally in a menagerie or internally in the darker part of their psyches. What may clinch this intriguing correspondence is the running of these cartoon shorts in consecutive episodes of the original Bugs Bunny/Road Runner Hour.

It may be said to be something of a stretch to advance an argument for correspondence between "Tweety's Circus" and "Hyde and Go Tweet" to this extent. Suffice it to say, then, that in the former cartoon, Sylvester meets his own savage ancestor, and in the latter cartoon, he meets Tweety's- and the circumstances of both, however different in setting and effect, suggest a recurring motif- the bestial ancestor of both characters lurking either externally in a menagerie or internally in the darker part of their psyches. What may clinch this intriguing correspondence is the running of these cartoon shorts in consecutive episodes of the original Bugs Bunny/Road Runner Hour.

It is also noteworthy that instalment 23 of The Bugs Bunny/Road Runner Hour, which preceded instalment 24 with "Hyde and Go Tweet", also contained "Pre-Hysterical Hare" in which Bugs witnesses his ancestor, the Sabre-Toothed Rabbit, via a long-preserved film of Stone Age life recovered and viewed by Bugs. Moreover, on Canada's cross-country CBC Television network, in February, 1974, It's a Mystery, Charlie Brown, wherein Woodstock's twig-constructed home is confiscated for Sally's school science exhibit as a prehistoric bird's nest, was shown on the Monday evening between these instalments of The Bugs Bunny/Road Runner Hour broadcast on Saturday, February 16 and Saturday, February 23. A curious coincidence!

Sylvester has become a humanised cat with a psychological "hang-ups" over his catly instinct to chase, catch, and eat birds. Each time that he succumbs to this urge, he reverts to the lion or wildcat within him. As the killing-is-wrong credo is "drilled" into his head by repetitious umbrella strikes by Granny or by the moralising of other cats, he increasingly finds himself in conflict with himself. Shame is what causes his "other self" to assume the menacing, Hyde-like monstrous aspect of the ravenous lion, something to be fled, or combated and vanquished. But Sylvester is unable to overcome his "lion problem", the shame persists, and in later cartoons, he becomes neurotic with guilt or self-doubt.

Sylvester has become a humanised cat with a psychological "hang-ups" over his catly instinct to chase, catch, and eat birds. Each time that he succumbs to this urge, he reverts to the lion or wildcat within him. As the killing-is-wrong credo is "drilled" into his head by repetitious umbrella strikes by Granny or by the moralising of other cats, he increasingly finds himself in conflict with himself. Shame is what causes his "other self" to assume the menacing, Hyde-like monstrous aspect of the ravenous lion, something to be fled, or combated and vanquished. But Sylvester is unable to overcome his "lion problem", the shame persists, and in later cartoons, he becomes neurotic with guilt or self-doubt.

"Tweet Dreams" (1959) has him in a psychologist's office, frustrated by his inability to catch Tweety, plagued by feelings of weakness or inferiority, which have him on the verge of total mental breakdown. Sylvester has been unable to assuage his craving for canary, has been told by humans and by fellow cats that he should not do so, and has reached the point of wanting to be rid of Tweety just for peace of mind, but Tweety- and the desire associated with the canary- keeps returning to Sylvester's life, prompting the cat to resume his chase and suffer further failures and continued culpability. As a humorous twist at this cartoon's closure, the doctor after listening to Sylvester suffers a neurosis. He flies away from his office like an undomesticated bird, with Sylvester doing the identical thing in pursuit of the psychiatrist. Sylvester becomes a bird, with the "beastly" ability to fly; he does what Tweety will do as the monster in his "Hyde and Go Tweet" nightmare (day-mare), an ungraceful regression of Tweety as imagined by Sylvester that follows from anguish suffered by Sylvester from his own reverting tendencies. It is intriguing foreshadowing, in that "Hyde and Go Tweet" in production order follows this cartoon short, and it strengthens the theory of connection between Tweety and Sylvester, between the problem posed by "domestication" to each of them.

The Jekyll-Hyde story is a classic portrayal of release of human regressive urges. In a couple of Sylvester's cartoons without Tweety, also directed by Freleng, he is forced to do battle with two belligerent dogs, Spike and Chester. In one cartoon, he is assisted by a black panther escaped from the zoo; in the other, Sylvester himself becomes the wildcat, by mistaken consumption of Hyde formula, and rather gleefully claws bulldog Spike into little pieces. In different cartoons, both Sylvester and Tweety experience the potion-induced regression to the animal from which they have evolved, and the loss of their humanly evolved or "domesticated" traits being accompanied by a monstrous change of appearance and character.

The cage, for Sylvester or for Tweety, seems to signify a dichotomy  between safety and shame. It is a physical means of securing them from the outside world and its wildness, thereby permitting their domestication, while also leading to psychological problems concerning the lingering potential wildness within their instinctual minds. For Sylvester in "Tweety's Circus", a cage is a presumed way of escaping the lion(s). Yet, he finds that he has locked himself inside of it with them, which seems to symbolise that he is not safe from them in his own mind. The lion is with him there. Tweety has become "A Bird in a Guilty Cage", to quote the comical title of one of his 1952 cartoons. The cage shelters him from the wild outside but not inside of his mind. A physical reverting to the wild bird is accompanied by notions of fall from grace a la Jekyll and Hyde. The cage may thus represent human civilisation, the imposing of which over the two characters has robbed their state of nature of its innocence and rendered any return to it ignoble or shameful.

between safety and shame. It is a physical means of securing them from the outside world and its wildness, thereby permitting their domestication, while also leading to psychological problems concerning the lingering potential wildness within their instinctual minds. For Sylvester in "Tweety's Circus", a cage is a presumed way of escaping the lion(s). Yet, he finds that he has locked himself inside of it with them, which seems to symbolise that he is not safe from them in his own mind. The lion is with him there. Tweety has become "A Bird in a Guilty Cage", to quote the comical title of one of his 1952 cartoons. The cage shelters him from the wild outside but not inside of his mind. A physical reverting to the wild bird is accompanied by notions of fall from grace a la Jekyll and Hyde. The cage may thus represent human civilisation, the imposing of which over the two characters has robbed their state of nature of its innocence and rendered any return to it ignoble or shameful.

In conclusion, there would seem to be depth to the cartoons featuring the duo of Tweety and Sylvester, because the idea of domestication creating "hang-ups" and complexes in the psyches of these two characters seems to carry rather interesting meaning in the way that it is portrayed in various of the 42 cartoons in the series.

Tweety and Sylvester Filmography

Sequence of Tweety and Sylvester Cartoons in The Bugs Bunny/Road Runner

Hour (1968-9)